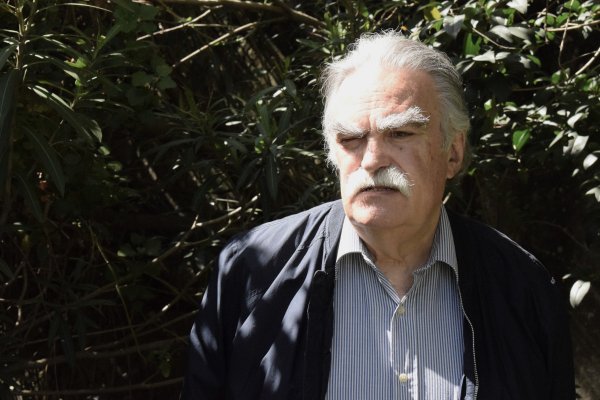

Víctor Giorgi - General Director, Inter-American Children’s Institute (IIN-OAS)

Víctor Giorgi is a Uruguayan psychologist and current Director General of the Inter-American Children’s Institute (IIN). As the Organization of American States’ (OAS) specialised body on children and adolescents, the IIN assists States with the development of public policy and supports its implementation, based on the promotion, protection, and respect for the rights of children and adolescents.

Mr. Giorgi began his professional career as a professor of the Faculty of Psychology at the University of the Republic (UDELAR – Uruguay), where he also served as dean between 1999 and 2005, and currently serves as Academic Coordinator of UDELAR’s Master’s Degree Programme in Children’s Rights and Public Policy. Prior to joining the IIN, he was also president of the Uruguayan Children’s Institute (INAU) from 2005-2009. He has authored a significant number of articles on topics related to his area of expertise, including children’s policy, health, social and community psychology, and children’s rights.

The IIN “assists States with developing public policy, contributing to policy design and implementation from the perspective of the promotion, protection and respect for the rights of children and adolescents.” In what ways does the IIN carry out this assistance mainly?

The technical assistance that the IIN offers to the Member States of the Inter-American System takes different forms that complement each other according to each State’s demand and the possibilities available. The processes may involve supporting the development and implementation of projects in the medium or long term as part of the design of public policies.

Furthermore, work is carried out on the production of knowledge, the systematisation and analysis of experiences, the critical study of normative frameworks, and the creation of intervention tools and mechanisms. To this end, talks are carried out between the States’ liaison officers so as to share experiences and extract lessons.

One of the principal activities carried out by the IIN in coordination with the States is the training of professionals via distance and blended learning courses which reach all Inter-American System countries.

To sustain and strengthen these actions, agreements are made with strategic partners from civil society and academia.

It will soon be ten years since the IIN published its position paper “Adolescent Criminal Liability Systems in the Americas” (2012). This paper is in favour of prioritising the socio-educational component over the punitive with regards to the treatment of adolescents in conflict with the law. Do you think that the socio-educational element takes precedent in the adolescent criminal responsibility systems of this region today?

Unfortunately, the security policies implemented in this region use prison as the main recourse, since socio-educational components are not well developed. Despite this, there are some very interesting experiences, but always on a small scale and oftentimes without the duration that would allow us to evaluate results in the medium and long term.

Although socio-educational measures show lower percentages of recidivism, there is a social pressure on judicial operators that makes it difficult to apply them on a large scale.

The IIN has recently launched a report with guidelines for the prevention and management of institutional violence within juvenile justice systems. What mechanisms or measures used by Member States of the OAS would you highlight as being the most effective to prevent such violence?

Violence within these systems has two sources that reinforce one another: violence among peers, especially when there are gangs, and institutional violence by officials or institutional representatives.

In this regard, most of the States have regulations and protocols to deal with these situations. A small percentage have preventative programmes directed at staff in the centres or towards other authorities, or preventative programmes directed at adolescents. Others have training and specialisation programmes directed at the officials in contact with young people in conflict with the law.

Regarding mechanisms of surveillance, control, and supervision, and/or bodies whose role it is to visit and inspect such detention centres, most have internal mechanisms – that is, the centres themselves process possible complaints, with the difficulties that this entails in terms of offering guarantees to the complainants.

In responding to allegations, two types of measures can be identified: those aimed at safeguarding the lives and personal integrity of victims, and those linked to an investigation or punishment of those responsible.

What assessment would you make of the ability of the continent’s juvenile justice systems to adequately treat social groups that often suffer structural discrimination, such as girls and young women based on their gender, or young people who are LGBTQI+?

The gender dimension has only very recently entered the logic of adolescent criminal responsibility systems. The organisation of the system is based on a binary sexual differentiation, without scope to consider the singularities that break away from the male/female dichotomy. This leads to situations of institutional violence that particularly affect LGBTQI+ young people.

The difference between biological sex and gender identity disrupts the system’s usual responses and this is usually resolved through the imposition of expected behaviours based on biological identity, ignoring gender identity and people’s self-perception.

This occurs even in countries where adolescents have their right to modify their original gender identity recognised, but this is not usually respected within criminal responsibility systems.

Additionally, in recent years there has been a sustained increase in female adolescents within the system, which makes it necessary to rethink certain aspects of institutional organisation in order to contemplate the particular needs related to their gender. Related to this is the situation of mothers who live with their children within the establishments, and pregnancies.

What policies or measures implemented in Member States of the OAS would you highlight for their effectiveness in keeping children and young people away from crime and from contact with the juvenile justice system?

The inequity and violence that persist across the American continent are difficult to reverse with isolated actions that do not modify structural aspects.

A relevant component of these policies is access and retention within the education system. Although this had been seeing an increase, the situation associated with the COVID-19 pandemic led to long periods of closure in education centres and the implementation of “remote” learning arrangements that left a significant number of children and young people behind. In the adolescent bracket, there is talk of a 50% disaffiliation from the education system. This, along with the discrimination that decreases chances of social integration, leads us to think that the coming years will especially difficult in terms of the different expressions of violence at a social level.